A recent

blog post on Watts Up With That? was titled, Raise your hand if you knew

Newfoundland was devastated by a major tsunami in 1929. I had to raise my

hand because, probably like many other people, I did not know that.

This is one

of those stories that is close to home (at least it is in Canada, if on the

other side of the country) which too often we do not study about enough. When I

got to looking up the event, I discovered that there is quite a lot of

information about the event along with considerable scientific research on the

physical aspects of this tsunami and tsunamis in general using this example.

The 1929 tsunami was the result of a magnitude 7.2 earthquake and subsequent slump of debris in the Laurentian Channel on 18 November 1929. The centre of the disturbance was about 150 miles south of Newfoundland.

Map showing

intensity of earthquake felt throughout Maritime Canada from 2011 report by

Natural Resources Canada

The tsunami generated by the earthquake struck southern Newfoundland about two and a half hours after the event. It came in three pulses causing sea level to rise over 20 feet. At the heads of inlets, the water was over 40 feet higher than normal. According to the government report, “In more than 40 villages in southern Newfoundland homes, ships and businesses were destroyed. More than 280,000 pounds of salt cod were lost. Total property losses were estimated at more than one million 1929 dollars [$14.5 million today].”

|

Map showing

extent of damage along the Burin Peninsula of Southern Newfoundland from 2011

report by Natural Resources Canada

The Burin

Peninsula had been isolated prior to the earthquake when a storm the previous

weekend had broken the one strand of telegraph wire that connected the area to

the rest of the province. The tsunami took care of the rest of the

communications infrastructure along the southern coast.

Some damage

from the earthquake and tidal wave had been reported in towns further up

Placentia Bay to the northeast, but news of the disaster along Burin Peninsula

was not relayed for over two days. Newspapers across the country shouted

reports of the disaster which had killed 27 people and caused untold

destruction.

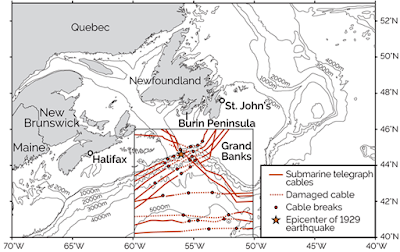

Because of the market crash the previous month, much attention from the news media was being directed at the international economy. What was happening in the natural world did not get much notice. And being cut off from the world by broken telegraph lines on land and submerged cables running across the ocean floor of the Grand Banks. Over several hours following the earthquake, 12 trans-Atlantic cables were cut.

|

Map showing location of broken cables resulting from

the earthquake and debris flows; source Earth

Magazine website

Eventually

the world heard about the disaster and relief came in the form of food,

blankets, medical supplies, and doctors and nurses. Some areas partially

recovered, in terms of infrastructure at least, in a few years; others never did.

Many families were impacted and a few entirely wiped out.

These kinds

of events are not unique. They have happened along coastal margins for hundreds

of millions of years. They achieve notoriety when communities are destroyed,

and people are killed. Some events may go unnoticed by the outside world for

years because of competing news stories, their remote location or, in this

case, the break in communications.

No comments:

Post a Comment